Balancing the rotating assembly has absolutely nothing to do with damping the torsional vibrations created with each power stroke. They are completely different things. It can't be said enough. A dynamically unbalanced rotating assembly will wobble and shake end-to-end (damaging the main bearings mostly in the process) and create a rough running engine. This issue can be almost completely prevented by balancing the rotating assembly.

Harmonic torsional vibrations are completely different from the forces you deal with on an unbalanced rotating assembly and need to be counteracted completely differently.

Each power stroke actually twists the crank shaft (pretend the crank is made of rubber). This doesn't create any wobbling or rough running of the engine (so adding a damper won't typically make the engine run any "smoother"). This twisting doesn't harm the main bearings either. The crank throw twists back and forth and hopefully by the time the piston experiences another power stroke the twisting has stopped, or is at least counteracting the new twisting force about to be applied by the new power stroke. If the twisting is in the wrong direction the power stroke will add to it again creating a resonant effect where if maintained at that engine load and rpm you can potentially snap the crank shaft. That is why dampers are installed from the factory; to prevent the crank shaft from snapping at resonant rpm. This rpm is different for all motors based on crank material and construction, crank throw, and crank length. The longer the throw, the longer the crank, and the poorer the construction the worse off you are with twisting forces and potential for catastrophe. A proper damper is designed to stop the twisting mostly around the resonant rpm (always in multiples of rpm for example 3k and 6k and 9k and 12k rpm). The main risk of undamped twisting is crankshaft failure. You also have trouble with ignition and cam timing being incorrect as the piston will be sooner or later than expected due to the twisting of the crank.

There is argument about how much damage this twisting can do to the rod bearings (no damage to main bearings at all). Some will argue there shouldn't be much damage to the rod bearings as the forces involved are no greater than those normally experienced by the power stroke.

Others will point out that the twisting and rebounding of the crank isn't much of an issue but you run into problems when the rebounding twist runs into a power stroke and they counteract. That will put about twice the force normally experienced by the bearings and could flatten the bearings or break the oil film. (This would be at the non-resonant rpm such as 1.5k and 4.5k and 7.5k and 10.5k and 13.5k).

Also the fact that the crank journal bounces back and forth instead of just traveling in one continuous direction could also place higher compression forces on the rod bearings than under normal conditions.

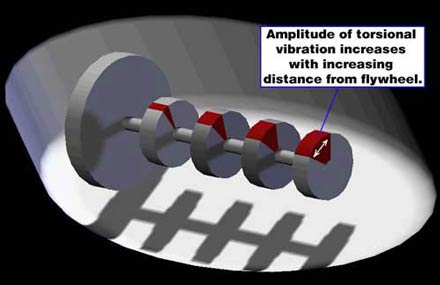

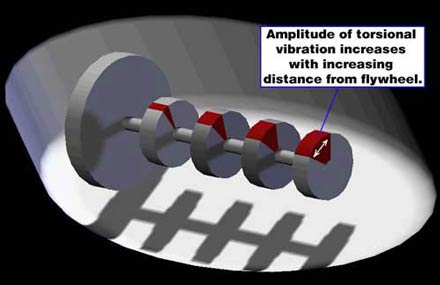

I will leave you with a few images that should help send home the message.

This is why dampers are almost universally attached to the crank opposite the flywheel.

I don't mean to sound like a damper salesman, but there is too much misinformation about this hard-to-understand topic that I wanted to clear up.

Also, I don't think these dampers are completely necessary for all engines and builds. The OEM damper can be removed with an aluminum pulley replacement and you can have an engine that works for your needs. You can use the OEM damper, or you can go with an upgraded unit. It's just a matter of what you want to accomplish with your build and what risks you're willing to take. Things like sprung clutch hubs also have a big effect on how much torsional springing you have to deal with on the crank. (A sprung hub can help reduce the amplitude of the twisting or move the resonant windows far enough apart to avoid any issues.)

And then there are engines with dual-mass flywheels (BMW inline-6 engines come to mind) which are designed to prevent the crankshaft from having a solid mounting with which to build up torsional forces to begin with, preventing as much twist from developing as possible to give the damper on the other end of the crankshaft a much easier job. This is more important on longer crankshafts, like those used on inline-6 engines and similar, since they experience more torsional twisting (because of their increased length).

Harmonic torsional vibrations are completely different from the forces you deal with on an unbalanced rotating assembly and need to be counteracted completely differently.

Each power stroke actually twists the crank shaft (pretend the crank is made of rubber). This doesn't create any wobbling or rough running of the engine (so adding a damper won't typically make the engine run any "smoother"). This twisting doesn't harm the main bearings either. The crank throw twists back and forth and hopefully by the time the piston experiences another power stroke the twisting has stopped, or is at least counteracting the new twisting force about to be applied by the new power stroke. If the twisting is in the wrong direction the power stroke will add to it again creating a resonant effect where if maintained at that engine load and rpm you can potentially snap the crank shaft. That is why dampers are installed from the factory; to prevent the crank shaft from snapping at resonant rpm. This rpm is different for all motors based on crank material and construction, crank throw, and crank length. The longer the throw, the longer the crank, and the poorer the construction the worse off you are with twisting forces and potential for catastrophe. A proper damper is designed to stop the twisting mostly around the resonant rpm (always in multiples of rpm for example 3k and 6k and 9k and 12k rpm). The main risk of undamped twisting is crankshaft failure. You also have trouble with ignition and cam timing being incorrect as the piston will be sooner or later than expected due to the twisting of the crank.

There is argument about how much damage this twisting can do to the rod bearings (no damage to main bearings at all). Some will argue there shouldn't be much damage to the rod bearings as the forces involved are no greater than those normally experienced by the power stroke.

Others will point out that the twisting and rebounding of the crank isn't much of an issue but you run into problems when the rebounding twist runs into a power stroke and they counteract. That will put about twice the force normally experienced by the bearings and could flatten the bearings or break the oil film. (This would be at the non-resonant rpm such as 1.5k and 4.5k and 7.5k and 10.5k and 13.5k).

Also the fact that the crank journal bounces back and forth instead of just traveling in one continuous direction could also place higher compression forces on the rod bearings than under normal conditions.

I will leave you with a few images that should help send home the message.

This is why dampers are almost universally attached to the crank opposite the flywheel.

I don't mean to sound like a damper salesman, but there is too much misinformation about this hard-to-understand topic that I wanted to clear up.

Also, I don't think these dampers are completely necessary for all engines and builds. The OEM damper can be removed with an aluminum pulley replacement and you can have an engine that works for your needs. You can use the OEM damper, or you can go with an upgraded unit. It's just a matter of what you want to accomplish with your build and what risks you're willing to take. Things like sprung clutch hubs also have a big effect on how much torsional springing you have to deal with on the crank. (A sprung hub can help reduce the amplitude of the twisting or move the resonant windows far enough apart to avoid any issues.)

And then there are engines with dual-mass flywheels (BMW inline-6 engines come to mind) which are designed to prevent the crankshaft from having a solid mounting with which to build up torsional forces to begin with, preventing as much twist from developing as possible to give the damper on the other end of the crankshaft a much easier job. This is more important on longer crankshafts, like those used on inline-6 engines and similar, since they experience more torsional twisting (because of their increased length).

Last edited by BenFenner

on 2021-09-09

at 09-26-58.

Back to top

Back to top